Today is the 129th anniversary of the U.S. publication of Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, another installment in the novelization with great embellishment of the childhood of Samuel Clemens in Hannibal, Missouri, before the Civil War. Earlier installments included The Adventures of Tom Sawyer.

Cover and binding of the first edition of Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Mark Twain was the pen name of Samuel L. Clemens. Wikipedia image

It is THE great American novel. It is the novel in which America faces its coming-of-age, in the metaphysical ramblings of a 13-year-old boy in the dark, on a raft in the Mississippi River, with an escaped slave who is a good friend, and has saved his life. Huck Finn confronts reality: Should he do what the preachers say to do, or should he do the moral thing instead?

America, most of it, grew up with that realization, coming even as it did, a generation after the Emancipation Proclamation.

In a good school, one probably unaffected by the damage done to learning by George Bush’s “No Child Left Behind Act,” nor more recent purges of quality in the classroom such as “value-added teaching,” “Racing to the Top,” or Common Core State Standards or the folderol conservative backlash against education in general, Tom Sawyer is often a child’s introduction to Twain, and to book-length literature.

In my youth, Tom Sawyer was so popular with teachers, and reading aloud by teachers was considered such a great idea, I think I heard the book three times. I know Mrs. Eva Hedberg, in my third grade class in Burley, Idaho, read parts of it. My recollection is that Mrs. Elizabeth Driggs and Mr. Herbert Gilbert both read it to us, in fourth and fifth grade, in Pleasant Grove, Utah. (There were other books; I think I heard five of the Laura Ingalls Wilder books between those three teachers. Reading was golden to them. Mrs. Hedberg even gave me credit for reading encyclopedia, cover to cover, with each letter of the alphabet counted as a book. Our World Book volume for the letter S had disappeared; I’ve never been good at snakes.)

Twain once remarked that he didn’t think a youth could read the Bible and ever draw a clean, fresh breath of air again. Tom Sawyer can similarly haunt the life of a person, though generally to higher moral standards.

I had hoped they’d continue to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. When they didn’t, I borrowed it from the Pleasant Grove Junior High Library and read it through. I read it in the middle of the modern civil rights struggle, between 1963’s horrors and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, just as our Vietnam tragedy was really ramping up.

Wait. I remember Mr. Gilbert being stopped by a question on Huck’s father, Pap. This was in Deep Mormonia, in Utah County. Pap drank a bit. Well, that’s not accurate. Pap drank to excess, often. Most of my fellow students had no knowledge of the drinking of alcohol. Their parents didn’t drink, not in front of the children if they did, since imbibing alcohol was a violation of the LDS Church’s Word of Wisdom, a commandment that they treat their bodies as temples, not as amusement parks. That bodily purity rule put alcohol, tobacco and caffeine off-limits. Most of the parents simply didn’t drink. It would have put sugar off-limits, too, had there been enough sugar to abuse as late-20th century America did. Also, there was the issue of the LDS Church having significant holdings in the U & I Sugar Company (Utah and Idaho), which made sugar from beets, and blessed the church with a significant stream of income, from the Coca-Cola bottlers alone. But I digress.

Maybe we did hear some of Huck Finn. I didn’t hear all of it — mumps, or something. And I checked it out on my own later.

One line jumped out at me from the start. It is a powerful lesson in government and democracy.

In the course of the novel, Huck falls in with a couple of crooks, the Duke and the King. They make their swindles in land deals on lands to which they don’t have title.

In Chapter XXVI (26), Huck accompanies the two swindlers to an orphanage of sorts. The duke and the king decide to sell the orphanage, and leave town before their purchasers discover the sales are frauds. Early on in their hustings they collect a bag of gold. Then Huck sits down to dinner with one of the girls at the place, and he meets a few others who all treat him rather kindly, and in the course of an hour or two he begins to have second thoughts, fearing for the fate of the orphans.

Meanwhile with investments coming in so fast, the duke and the king ponder leaving town earlier than planned, with at least the bag of gold, fearing they might be discovered. In the course of their conversation, overheard by Huck hiding in the room, the king works to convince the duke that most of the town’s people remain bamboozled:

Well, the king he talked him blind; so at last he give in, and said all right, but said he believed it was blamed foolishness to stay, and that doctor hanging over them. But the king says:

“Cuss the doctor! What do we k’yer for him? Hain’t we got all the fools in town on our side? And ain’t that a big enough majority in any town?”

Savor that one, and let it sink in for a bit. “Hain’t we got all the fools in town on our side? And ain’t that a big enough majority in any town?”

James Madison and Thomas Jefferson trafficked in democratic institutions at a metaphysical level, understanding men were no angels, as Madison put it, but with a bit of education a people should be able to rule themselves as well as, or better than, a tiny elite, even if that elite were educated. But they understood at the wholesale political level that a check was necessary on the people; in 1822 Madison defended free public education in a letter:

A popular Government, without popular information, or the means of acquiring it, is but a Prologue to a Farce or a Tragedy; or perhaps both. Knowledge will forever govern ignorance. And a people who mean to be their own governours, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.

In Huck Finn, just over a half-century later, Twain was writing about applied politics, the theory, not the hypothesis, on a retail level. Without education for the masses, the group who cynically bamboozles for money or power wins once they’ve got every fool in town on their side.

We have a political system that is more subject to corruption due to lack of education than lack of money.

To an honest politician, this is a huge burden. You won the election? You got the vote of every fool in town? Then it’s up to you to act wisely, despite their foolishness. Robert Redford’s character in “The Candidate” pulls an upset win in a U.S. Senate race — the film closes with the candidate, rather scared, sitting down with the party-provided campaign advisor, and asking in all earnestness: “What do we do now?”

Happy anniversary, Huck Finn. Perhaps we should fly the flag today in honor of the publication of the book. We would fly it a bit nervously, perhaps.

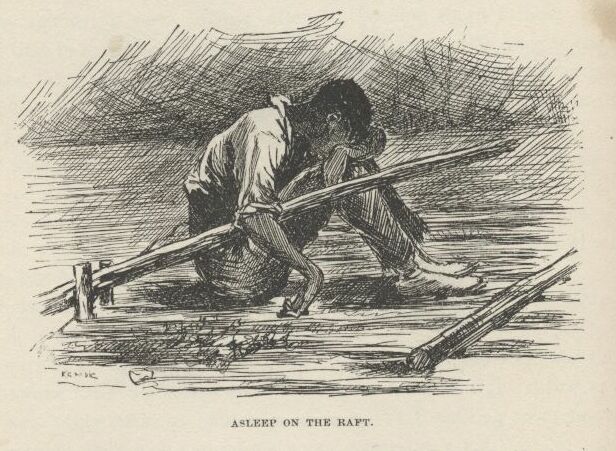

Twain himself hired E. W. Kemble to illustrate the first edition.

Or at least drink a toast to Huck. Hooray.

LikeLike