James Madison, the fourth President of the United States, and the Father of the Constitution, was born March 16, 1751, in the Tidewater area of Virginia.

Is it sinful that we do not celebrate his birthday with a federal holiday, fireworks, picnics and speeches and concerts?

Maybe you could fly your flag today. If the neighbors ask why, tell them you’re flying it for freedom on James Madison’s birthday. They’ll say, “Oh,” and run off to Google Madison. You will have struck a blow for the education that undergirds democracy.

Journalists honor Madison on his birthday, and through the week in which his birthday occurs, with tributes to the First Amendment which he wrote, and celebrations of Freedom of Information Laws and press freedoms, two issues dear to Madison’s heart.

There is much, much to celebrate about him.

A few years ago I was asked to talk about freedom to a group of freedom lovers in North Texas. I chose to speak about James Madison’s remarkable, and too-often unremarked-upon life. Later, when I started this blog, I posted it here, with an introduction. All of that is below, in honor of the birth of James Madison.

Did you know that Madison is the shortest man ever to have been president? His stature is measured in freedom, not in feet and inches.

(Originally a post on July 31, 2006)

James Madison, 1783, miniature by Charles Wilson Peale. Madison would have been 32. Library of Congress collection

I don’t blame students when they tell me they “hate history.” Heaven knows, they probably have been boringly taught boring stuff.

For example, history classes study the founding of the United States. Especially under the topical restrictions imposed by standardized testing, many kids will get a short-form version of history that leaves out some of the most interesting stuff.

Who could like that?

Worse, that sort of stuff does damage to the history and the people who made it, too.

James Madison gets short shrift in the current canon, in my opinion. Madison was the fourth president, sure, and many textbooks note his role in the convention at Philadelphia that wrote the Constitution in 1787. But I think Madison’s larger career, especially his advocacy for freedom from 1776 to his death, is overlooked.

Madison was the “essential man” in the founding of the nation, in many ways. He was able to collaborate with people as few others could, in order to get things done, including his work with George Mason on the Virginia Bill of Rights, with George Washington on the Constitution and national government structure, Thomas Jefferson on the structure and preservation of freedom, Alexander Hamilton on the Constitution and national bank, and James Monroe on continuing the American Revolution.

We need to look harder at the methods and philosophy, and life, of James Madison. This is an opinion I’ve held for a long time. Below the fold I reproduce a “sermon” I delivered to the North Texas Church of Freethought in November 2001.

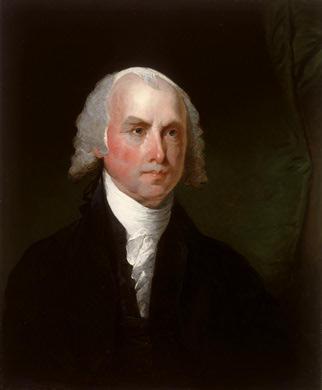

James Madison’s official White House portrait, by John Vanderlyn in 1816; in the White House collection

I have left this exactly as it was delivered, though I would change a few things today, especially emphasizing more the key role George Washington played in pushing Madison to get the Constitution — a view I came to courtesy of the Bill of Rights Insitute and their outstanding, week-long seminar, Shaping the Constitution: A View from Mount Vernon 1783-1789. The Bill of Rights Institute provides outstanding training for teachers, and this particular session, at Washington’s home at Mount Vernon, Virginia, is well worth the time (check with the Institute to see whether it will be offered next year — and apply!). I am especially grateful to have had the opportunity to discuss these times and issues with outstanding scholars like Dr. Gordon Lloyd of Pepperdine University, Dr. Adam Tate of Morrow College, and Dr. Stuart Leibiger of LaSalle University, during my stay at Mount Vernon.

James Madison, portrait by Gilbert Stuart c. 1821; National Portrait Gallery

My presentation to the skeptics of North Texas centered around the theme of what a skeptic might give thanks for at Thanksgiving. (It is available on the web — a misspelling of my name in the program carried over to the web, which has provided me a source of amusement for several years.)

Here is the presentation:

Being Thankful For Religious Liberty

As Presented at the November, 2001 Sunday Service of The North Texas Church of Freethought

Historians rethink the past at least every generation, mining history for new insights or, at least, a new book. About the founders of this nation there has been a good deal of rethinking lately. David McCullough reminds us that John Adams really was a good guy, and that we shouldn’t think of him simply as the Federalist foil to Thomas Jefferson’s more democratic view of the world. Jefferson himself is greatly scrutinized, and perhaps out of favor — “American Sphinx,” Joseph Ellis calls him. The science of DNA testing shows that perhaps Jefferson had more to be quiet about than even he confessed in his journals. While Jefferson himself questioned his own weakness in his not freeing his slaves in his lifetime, historians and fans of Jefferson’s great writings wrestle with the likelihood of his relationship with one of his own slaves (the old Sally Hemings stories came back, and DNA indicates her children were fathered by a member of the Jefferson clan; some critics argue that Jefferson was a hypocrite, but that was Jefferson’s own criticism of himself; defenders point out that the affair most likely was consensual, but could not be openly acknowledged in Virginia at that time). Hamilton’s gift to America was a financial system capable of carrying a noble nation to great achievement, we are told – don’t think of him simply as the fellow Aaron Burr killed in a duel. Washington is recast as one of the earliest guerrilla fighters, and in one book as a typical gentleman who couldn’t control his expenses. Franklin becomes in recent books the “First American,” the model after which we are all made, somehow.

Of the major figures of these founding eras, James Madison is left out of the rethinking, at least for now. There has been no major biography of Madison for a decade or more, not since Ralph Ketcham’s book for the University of Virginia press. Madison has a role in Joseph Ellis’s Founding Brothers, but he shares his spotlight with Hamilton and Jefferson. I think this is an oversight. As we enter into the first Thanksgiving season of the 21st century, we would do well to take a look back at Madison’s life. Madison gives us a model of reason, and more important, a model of action coupled to reason. America’s founding is often depicted as a time of great thunder — if not the thunder of the lightning Ben Franklin experimented with, an experiment he parlayed into worldwide respect for Americans, it is the thunder of the pronouncements of Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence, or of George Washington, just generally thundering through history.

The use of a bolt of lightning as a symbol for this group is inspired, I think. I’m a great fan of Mark Twain, and when I see that bolt of electricity depicted I think of Twain’s observation:

“Thunder is good; thunder is impressive. But it is lightning that does the work.”

Thunder at the founding is impressive; where was the lightning?

I’d like to point out two themes that run through Madison’s life, or rather, two activities that we find him in time and again. Madison’s life was marked by periods of reflection, followed by action as a result of that reflection.

We don’t know a lot about Madison’s youth. He was the oldest son of a wealthy Virginia planter, growing up in the Orange County area of Tidewater Virginia. We know he was boarded out for schooling with good teachers – usually clergymen, but occasionally to someone with expertise in a particular subject – and we know that he won admission to Princeton to study under the Rev. John Witherspoon, a recent Presbyterian transplant from across the Atlantic. Madison broke with tradition a bit in attending an American rather than an English school. And after completing his course of study he remained at Princeton for another year to study theology directly under Witherspoon, with an eye toward becoming a preacher.

Witherspoon is often held up as an example of how religion influenced the founders, but he was much more of a rationalist than some would have us believe. He persuaded the young Madison that a career in law and politics would be a great service to the people of Virginia and America, and might be a higher calling. After a year of this reflection, Madison returned to Virginia and won election to local government.

In his role as a county official Madison traveled the area. He inspected the works of government, including the jails. He was surprised to find in jail in Virginia people accused of — gasp! — practicing adult baptism. In fact Baptists and Presbyterians were jailed on occasion, because the Anglican church was the state church of Virginia, and their practicing their faith was against the common law. This troubled Madison greatly, and it directed an important part of his work for the rest of his life. In January of 1774, Madison wrote about it to another prominent Virginian, William Bradford:

“Poverty and Luxury prevail among all sorts: Pride ignorance and Knavery among the Priesthood and Vice and Wickedness among the Laity. This is bad enough. But it is not the worst I have to tell you. That diabolical Hell conceived principle of persecution rages among some and to their eternal infamy the Clergy can furnish their Quota of Imps for such business. This vexes me the most of any thing whatever. There are at this time in the adjacent County not less than 5 or 6 well meaning men in close Gaol for publishing their religious Sentiments which in the main are very orthodox. I have neither patience to hear talk or think of any thing relative to this matter, for I have squabbled and scolded abused and ridiculed so long about it, to so little purpose that I am without common patience. So I leave you to pity me and pray for Liberty of Conscience to revive among us.”

By April, Madison’s views on the matter had been boiled down to the essences, and he wrote Bradford again more bluntly:

“Religious bondage shackles and debilitates the mind and unfits it for every noble enterprise.”

Madison must have done a fine job at his county duties, whatever they were, because in 1776 when Virginia was organizing its government to survive hostilities with England, Madison was elected to the legislative body.

Madison was 25, and still raw in Virginia politics. He was appointed to the committee headed by George Mason to review the laws and charter of the colony. Another who would serve on this committee when he was back from Philadelphia was Thomas Jefferson. George Mason was already a giant in Virginia politics, and by the time Madison got to Williamsburg, Mason had already completed much of the work on a bill of rights to undergird the new Virginia government. Madison noted that freedom of religion was not among the rights enumerated in Mason’s version — but it was too late, Mason said. The work was done.

Madison quietly went to work on Mason, in committee, over dinner, during social occasions — noting the great injustice of jailing people solely because of their beliefs, and urging to Mason that it did Virginia no good to keep these fathers from providing for their families.

Mason ultimately agreed to accept the amendment.

The pattern was set.

Perhaps a better example of this reflection and action cycle occurred nearly a decade later. By 1785 the war was over, independence was won, but the business of government continued. While serving as governor of Virginia, Thomas Jefferson had drafted about 150 proposals for laws, really a blueprint for a free government. About half of these proposals had been passed into law. By 1785, Jefferson was away from Virginia, representing the Confederation of colonies in Paris. Jefferson had provided several laws to disestablish religion in Virginia, and to separate out the functions of church and state. With Jefferson gone, however, his old nemesis Patrick Henry sought to roll back some of that work. Henry proposed to bring back state support for the clergy, for the stated purpose of promoting education. (Yes, this is the same battle we fight today for church and state separation.) After Jefferson’s troubled term as governor, Virginia turned again to Henry – Henry ultimately served six terms as governor. His proposal was set for a quick approval in the Virginia assembly. It was late in the term, and everyone wanted to get home.

Henry was, of course, a thundering orator of great note. Madison was a small man with a nervous speaking style, but a man who knew the issues better than anyone else in almost any room he could be in. Madison came up with an interesting proposal. Picking the religion for the state was serious stuff, he said. A state doesn’t want to pick the wrong religion, and get stuck with the wrong god, surely – and such weighty matters deserve widespread support and discussion, Madison said. His motion to delay Henry’s bill until the next session, in order to let the public know and approve, was agreed to handily.

You probably know the rest of this story. With a year for the state to reflect on the idea, Madison wrote up a petition on the issue, which he called a “Memorial and Remonstrance.” In the petition he laid out 15 reasons why separation of church and state was a superior form of government, concluding that in the previous 1,500 years, every marriage of church and state produced a lazy and corrupt church, and despotic government. Madison’s petition circulated everywhere, and away from Patrick Henry’s thundering orations, the people of Virginia chose Madison’s cool reason.

When the legislature reconvened in 1786, it rejected Henry’s proposal. But Madison’s petition had been so persuasive, the legislature also brought up a proposal Thomas Jefferson had made six years earlier, and passed into law the Virginia Statue for Religious Freedom.

This was a great victory for Madison, and for Virginia. He celebrated by convening a convention to settle disputes between Virginia and Maryland about navigation on the Chesapeake Bay. Having reflected on the nature of this issue — a dispute between colonies — Madison had sought advice from others having the same problems, such as New York and New Jersey. In that effort he got the support of a New Yorker working on the same problems, Alexander Hamilton. In the course of these discussions Madison thought it clear that the difficulty lay with the form of government that bound the colonies together under the Articles of Confederation. Hamilton agreed, and they got their respective states and conferences to agree to meet in Philadelphia in 1787 to try to fix those problems. [Since I first wrote this, I’ve learned that it was George Washington’s desire to get a federal government, to facilitate the settling of the Ohio River Valley where Washington had several thousands of acres to sell, that prompted him to push Madison into the Annapolis Convention, and who made the introduction between Madison and Washington’s old aide and friend, Alexander Hamilton; Madison’s work with Washington runs much deeper than I orignally saw.]

James Madison, painted in 1792 by Charles Wilson Peale. Saatchi Gallery image

Amending the Articles of Confederation was a doomed effort, many thought. The colonies would go their separate ways, no longer bound by the need to hang together against the Parliament of England. Perhaps George Washington could have got a council together to propose a new system, but Washington had stayed out of these debates. Washington’s model for action was the Roman general Cincinnatus, who went from his plow to lead the Romans to victory, then returned to his farm, and finding his plow where he had left it, took it up again.

Madison invited Washington, and persuaded Washington to attend. Washington was elected president of the convention, and in retrospect that election guaranteed that whatever the convention produced, the colonies would pay attention to it.

You know that history, too. The convention quickly decided the Articles of Confederation were beyond repair. Instead, they wrote a new charter for a new form of government. The charter was based in part on Jefferson’s Virginia Plan, with lots of modifications. Because the Constitution resembles so much the blueprint that Jefferson had written, and because Jefferson was a great founder, many Americans believe Jefferson was a guiding light at that Philadelphia convention. It’s often good to reflect that Jefferson was in Paris the entire time. While America remembers the thunder of Washington’s presiding, Franklin’s timely contributions and Jefferson’s ideas, it was Madison who did the heavy lifting, who got Washington and Franklin to attend the meeting Madison had set up, and got Jefferson’s ideas presented and explained.

It was Madison who decided, in late August of 1787, that the convention could not hang together long enough to create a bill of rights, and instead got approval for the basic framework of the U.S. government. In Virginia a few months later, while Patrick Henry thundered against what he described as a power grab by a new government, it was Madison who assembled the coalitions that got the Constitution ratified by the Virginia ratifying convention. And when even Jefferson complained that a constitution was dangerous without a bill of rights, it was Madison who first calmed Jefferson, then promised that one of the first actions of the new government would be a bill of rights. He delivered on that promise as a Member of the House of Representatives in 1789.

It is difficult to appreciate just how deeply insinuated into the creation of America was James Madison. In big ways and small, he made America work. He took the lofty ideas of Jefferson, and made them into laws that are still on the books, unamended and unedited, more than 200 years later.

When the ratification battle was won, when Madison had won election to the House over Patrick Henry’s strong objection, partly by befriending the man Henry had picked to defeat Madison, James Monroe, Madison could have savored the moment and been assured a place in history.

James Madison in 1804, by Gilbert Stuart. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Virginia. Gift of Mrs. George S. Robbins

That’s not what a lightning bolt does. Journeying to New York for the opening of the First Congress and the inauguration of Washington as president, Madison stopped off at Mount Vernon to visit with Washington, apparently at Washington’s request. In what was a few hours, really, Madison wrote Washington’s inaugural address. While there at Mount Vernon, Madison stumbled into a discussion by several others on their way to New York, wondering what high honorific to apply to the new president. “Excellency” was winning out over “Your highness,” until Washington turned to Madison for an opinion. Madison said the president should be called, simply, “Mr. President.” We still do.

Once in New York, Madison saw to the organizing of the Congress, then to the organizing of the inauguration. And upon hearing Washington’s inauguration address — which Madison had ghosted, remember — Congress appointed Madison to write the official Congressional response.

Years later, in Washington, Madison engineered the candidacy of Thomas Jefferson for president, and after Jefferson was elected, Madison had the dubious honor as Secretary of State of lending his name to the Supreme Court case that established the Supreme Court as the arbiter of what is Constitutional under our scheme of government, in Marbury v. Madison.

Wherever there was action needed to make this government work, it seemed, there was James Madison providing the spark.

James Madison was the lightning behind the thunder of the founding of America. We should be grateful that he lived when he did, where he did, for we all share the fruits of the freedoms he worked to obtain. And in this Thanksgiving season, let us look for appropriate ways to honor his work.

James Madison, 1829, portrait by Chester Harding. Montpelier House, Billy Hathorn. “In 1829, Madison came out of retirement to attend a convention for revising Virginia’s constitution. While there, he posed for this portrait by the Massachusetts painter Chester Harding.”

The Madisonian model of thoughtful reflection leading to action is one that is solidly established in psychological research. It is the model for leadership taught in business schools and military academies.

I would compare religious liberty to a mighty oak tree, under which we might seek shade on a hot summer day, from which we might draw wood for our fires to warm us in winter, or lumber to build great and strong buildings. That big oak we enjoy began its life long before ours. We enjoy its shade because someone earlier planted the seed. We enjoy our freedoms today because of men like James Madison.

How do we give thanks? As we pass around the turkey to our family, our friends, we would do well to reflect on the freedoms we enjoy, and how we got them.

Finally, remembering that someone had to plant those seeds, we need to ask: What seeds must we plant now for those who will come after us? We can demonstrate our being grateful for the actions of those who came before us by giving to those who come after us, something more to be grateful for. A life like Madison’s is a rarity. Improving on the freedoms he gave us might be difficult. Preserving those freedoms seems to me a solemn duty, however. Speaking out to defend those freedoms is an almost-tangible way to thank James Madison, and as fate would have it, there is plenty of material to speak out about. A postcard to your senators and representative giving your reasoned views on the re- introduction of the Istook Amendment might be timely now – with America’s attention turned overseas for a moment, people have adopted Patrick Henry’s tactic of trying to undo religious freedom during the distraction. I have had a lot of fun, and done some good I hope, in our local school system by asking our sons’ science and biology teachers what they plan to teach about evolution. Whatever they nervously answer — and they always nervously answer that question — I tell them that I want them to cover the topic fully and completely, and if they have any opposition to that I would be pleased to lend my name to a suit demanding it be done. We might take a moment of reflection to ponder our views about a proposed Texas “moment of silence” bill to be introduced, and then let our state representatives have our thoughts on the issue.

Do you need inspiration? Turn to James Madison’s writings. In laying out his 15-point defense of religious freedom in 1785, Madison wrote that separation of church and state is essential to our form of government:

“The preservation of a free Government requires not merely, that the metes and bounds which separate each department of power be invariably maintained; but more especially that neither of them be suffered to overleap the great Barrier which defends the rights of the people.”

How can we express our gratitude for such a foundation for religious liberty? Let loose a few lightning bolts, in remembrance of Madison.

Copyright © 2001 and 2006 by Ed Darrell. You may reproduce with attribution. Links added in May 2013.

More:

Spread the word; friends don't allow friends to repeat history.

Posted by Ed Darrell

Posted by Ed Darrell

create a bill of rights, Madison had to run for election to the U.S. House of Representatives. Henry thought he could block that, too, by picking James Monroe to run against Madison, and getting lots of support for Monroe. In the last debate, a good buggy ride away from their homes, the two men decided to share the fare. Monroe said Madison won the debate handily; Madison wasn’t sure. On the buggy ride back to their homes, at night on a very cold winter, the two got involved in a long discussion about the new government, the new nation, and their hopes and dreams about the future. Discussion was so engrossing that Madison failed to notice his nose was freezing. Fast friends ever after, Madison won the election; Madison introduced Monroe to Jefferson. Patrick Henry’s plan to frustrate the Constitution and the new government was thwarted. And Madison bore the scar the rest of his life.

create a bill of rights, Madison had to run for election to the U.S. House of Representatives. Henry thought he could block that, too, by picking James Monroe to run against Madison, and getting lots of support for Monroe. In the last debate, a good buggy ride away from their homes, the two men decided to share the fare. Monroe said Madison won the debate handily; Madison wasn’t sure. On the buggy ride back to their homes, at night on a very cold winter, the two got involved in a long discussion about the new government, the new nation, and their hopes and dreams about the future. Discussion was so engrossing that Madison failed to notice his nose was freezing. Fast friends ever after, Madison won the election; Madison introduced Monroe to Jefferson. Patrick Henry’s plan to frustrate the Constitution and the new government was thwarted. And Madison bore the scar the rest of his life.